For the past eight years, Alisha and I have been serving in missions in Europe, starting with Mennonite Mission Network while working at LCC International University in Eastern Europe. However, since 2017 we — along with our kid Asher — have been serving in Barcelona, which is on the Mediterranean coast of Spain in a region called Catalunya.

And, about the time we explain to folks that we serve as missionaries in Barcelona, people often give us “the look.” It’s a look that says, “What’s the punchline?” That look often turns skeptical when they find out there is none.

Pre-missions Josh and Alisha cerca 2009 practice digging wells at the Mennonite Church USA convention in Columbus, Ohio.

To be honest, about 10 years ago, Alisha and I would have reacted the same way. At that time, we were both moving seriously towards full-time mission work and, when asked for details, we were telling everyone about how we were going to serve in Central or South America.

After all, that’s what missions are, right? You go to the poor and either bring the gospel or assist with a social project like building a well. And, actually, that’s all true. But God was about to teach us something important about poverty.

It all started when Alisha and I decided it would be smart to serve together in some type of short-term, international mission project just to see how well we work in that kind of environment. The only option we could find that fit our time frame was a three-week trip to the Czech Republic to help with an English Camp. Honestly, this wasn’t a mission field we had given any thought to up to that point.

It’s worth explaining that, in Europe, it’s common for churches to host evangelical English camps during the summer as a way to connect with young people and share the gospel. And, because learning English is hugely desirable, these camps tend to be pretty popular with youth who don’t go to church, too.

Anyway, our job was to simply assist the local Czech church that was hosting the camp and to follow our instincts when it came to connecting with the campers. During those three weeks, we discovered two things: first, that we can indeed do the mission thing pretty well together, and second, there’s another kind of poverty: Spiritual Poverty.

Jesus Christ: Worst Oprah ever?

There’s a particular Bible story that comes to mind when I try to explain what Spiritual Poverty means. In Mark 2:1-5, we find the story of a man being lowered through the roof of the house where Jesus was teaching. Most notable is how Jesus responds:

“When Jesus saw their faith, he said to the paralytic, ‘Son, your sins are forgiven.’”

Chronologically, this story takes place at a point in Jesus’ ministry where he was already established as a healer and, based on the packed house, clearly word had spread. It doesn’t seem like a stretch to conclude the guy on the mat and his friends were going to Jesus to have his paralysis healed.

Imagine all the emotions he was feeling:

Hope and anticipation while heading towards the house.

Adrenaline pumping while laying on your mat and watching your friends grow more and more distant as they slowly lower you through the roof.

You see the most exciting, controversial rabbi in the region — a healer — and he acknowledges you. Every nerve and neuron in your body is firing at the same time as you watch him look at your friends, and then back at you.

And then Jesus as, "Your sins are forgiven.”

That would be like being on the Oprah show the week after she surprised her audience by gifting them with free cars and, instead, getting a gift card to Applebee’s. It’s cool because free food is awesome, but deep down not what you were hoping for. In our story, what did the man receive? Spiritual healing. Probably not what he was hoping for.

Back to the story, the scribes accuse Jesus of blaspheming “because only God can absolve sins.” Jesus replies:

“‘But so that you may know that the Son of Man has authority on earth to forgive sins’ — he said to the paralytic — ‘I say to you, stand up, take your mat and go to your home.’”

In other words, Jesus makes the man whole on the outside in order to show that he has made him whole on the inside. Clearly, the man’s spiritual health was important to Jesus — physically healing the man, who then takes his mat and walks away, almost feels secondary in this story.

Christendom: colonialism and spiritual poverty

This is one of the stories about Jesus that establishes something many Christians readily profess: God cares a whole bunch about what’s happening inside of us...maybe even more than the outside.

But, if that’s the case, why is it that peoples’ concept of missions tends to be exclusive to “third-world/poor” countries? The short answer is the fancy, five-dollar word “Christendom” — a phenomenon that, more than Alisha and I knew, was shaping our perspectives while we were learning about doing missions in the Czech Republic.

So what does Christendom mean?

Christendom refers to that predominantly white, Western form of Christianity that has been conquesting the world under the banner of salvation. It’s often historically marked by Emperor Constantine declaring Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire in the 4th century.

At its core, the Empire’s mode of operating was built around this idea of conquering “inferior” civilizations and “helping” them by indoctrinating them with “superior” Roman beliefs and culture. And they were really, really good at doing this. So much so that this mindset also permeated the way Christians operated.

“Some of those that work forces

Are the same that burn crosses”

The result has been centuries of Christian missions also taking the form of conquest and being used as a tool for colonization and empire. And, because of racism, non-Western cultures have almost always been viewed as the inferior ones that need saving.

[It’s probably not every day you read such a strong critique of global missions by a missionary and, honestly, it’s not my intention to harp on our missionary forebears. In fact, relatively speaking I think the Mennonites have done a pretty good job of ensuring dignity and respect are central to their approach to international missions.]

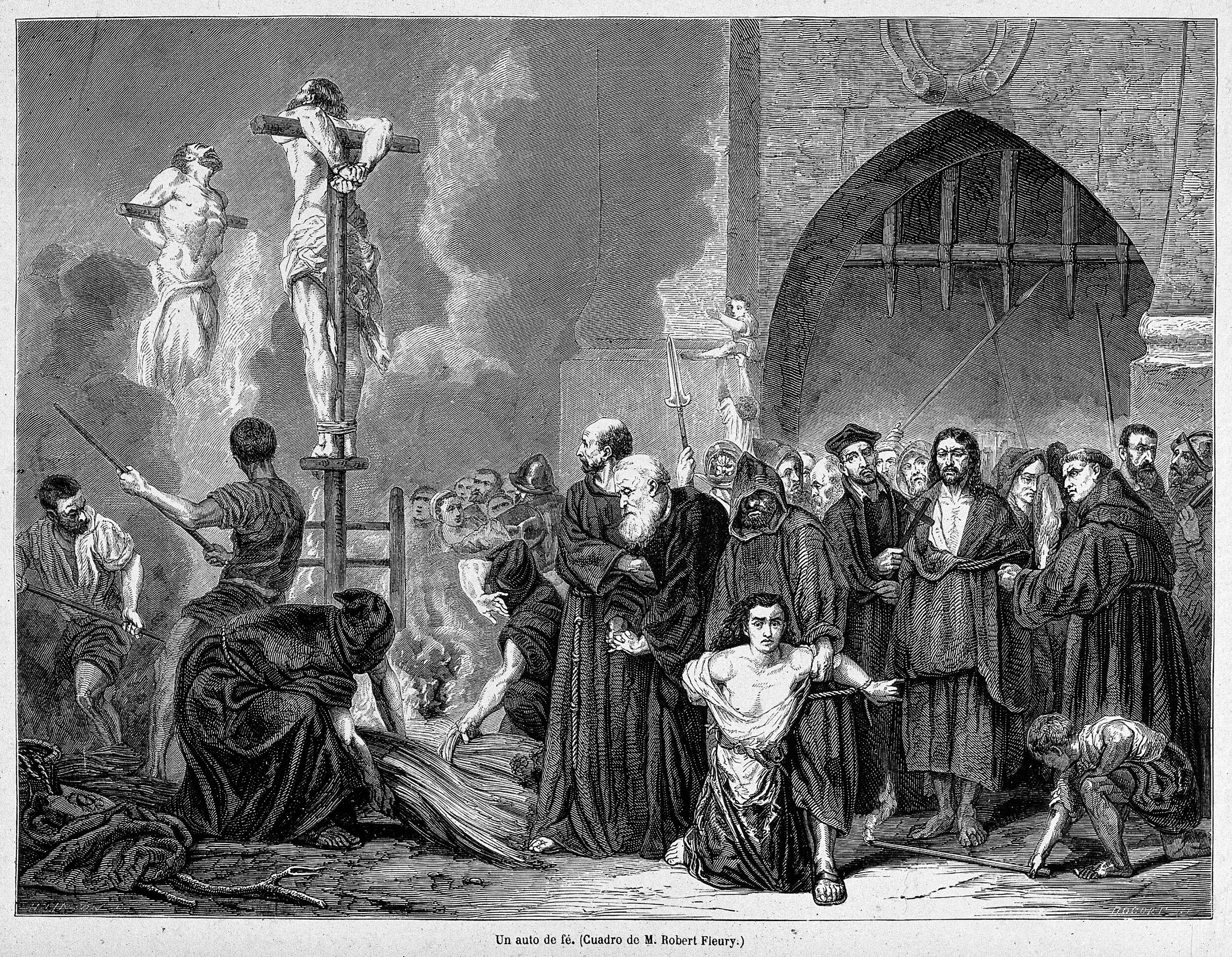

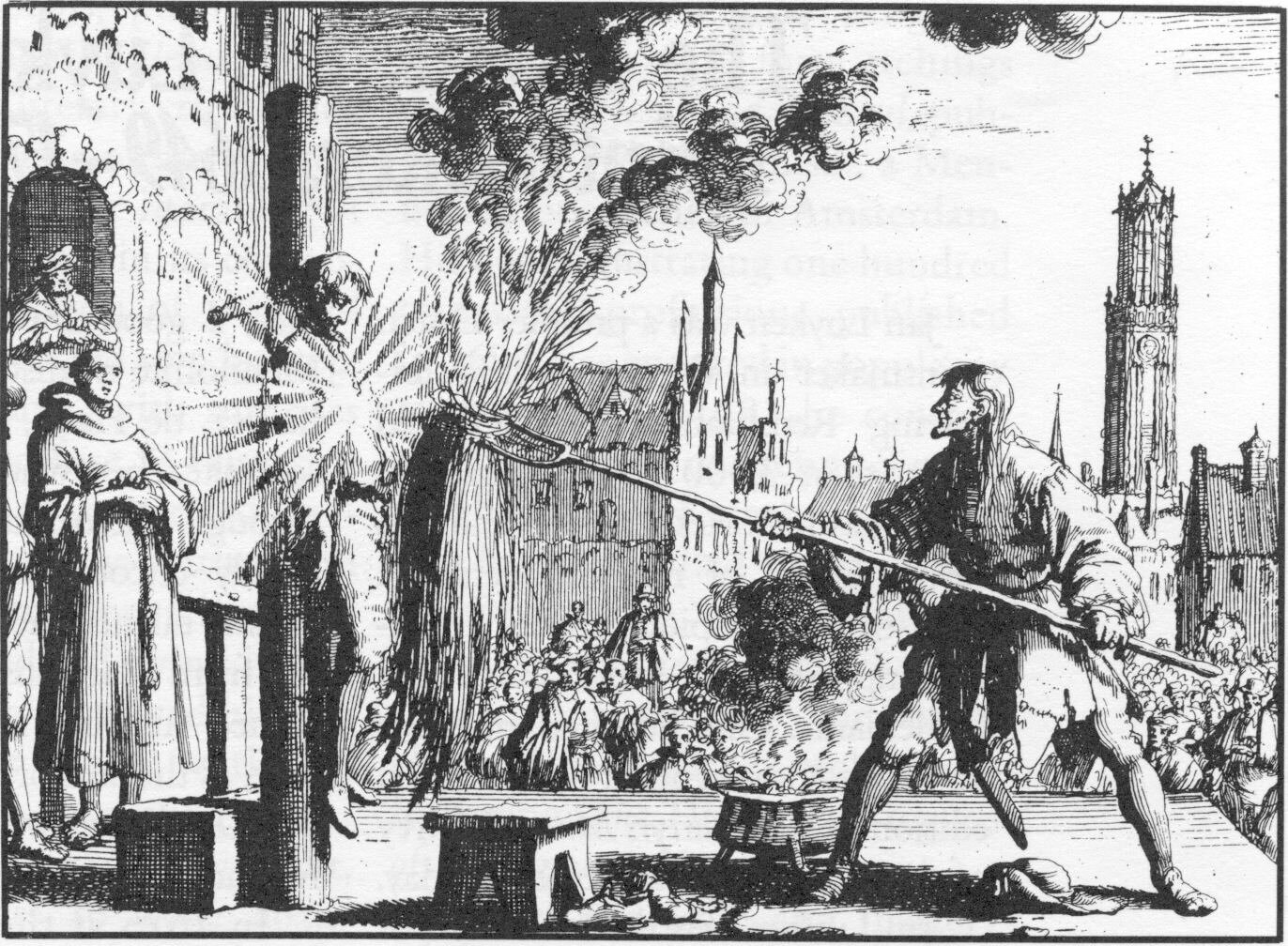

Throughout history, God’s message of love and redemption has transformed countless lives as a result of Christendom. Or maybe it’s better to say despite Christendom, because Christendom is also responsible for some of the most terrible parts of human history. Things like the Crusades, the Spanish Inquisition, the persecution of the early Anabaptists, and the literal genocide of two continents full of indigenous Americans.

These are just the most obvious of examples.

What’s really interesting is that for the past several decades, Europe has been moving into what is called the post-Christendom era. This implies that the time in which Christianity has acted as an extension of empire has ended. Of course churches and Christians still exist in Europe, so it’s not the same as saying “post-Christian,” but mainstream society has moved away from organized religion.

This means that when we arrived in the Czech Republic 10 years ago, we encountered young people who were feeling a deep spiritual longing but lacked the vocabulary or the guidance of healthy faith communities to find spiritual nourishment. And isn’t the definition of poverty not being able to get something you need to live fully?

Ergo, Spiritual Poverty.

Josh literally in the process of encountering post-Christendom in the Czech Republic.

The Czech English camp we helped with wasn’t put on by Mennonites and was flavored pretty strongly by North American Evangelical culture. That culture and perspective connected with some campers, but not all.

However, I remember going on a long hike with some of the youth and chatting with a group of them when they turned the conversation toward faith. When I shared about my faith perspective as an Anabaptist, there was an immediate response of interest. For most of the youth Alisha and I spoke with, institutional religion wasn’t appealing at all. However, a Jesus-centric faith-perspective that is meant to be lived out was extremely compelling.

People like Jesus.

This encounter changed the trajectory of our understanding of missions. We quickly learned our experience with the Czech youth wasn’t all that unique — post-Christendom has had a similar effect across the continent and, over the years of serving in Europe since then, our grasp of Spiritual Poverty has deepened.

One important lesson we’ve realized is that those who have the most privilege and wealth globally are often those who are the least connected to God and their faith. They rely on their own means and capabilities and think that inner peace and satisfaction can be obtained with the right combination of purchases.

This is why Jesus says:

“How hard it is for those who have wealth to enter the kingdom of God! Indeed, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God.”

Because of how missions were done in the past, it’s not always easy to see the missional needs that surround us in the present.

Post-Christendom missions in action

Now our journey has led us to Barcelona, where we’ve found the exact same spiritual longing and the same positive response to the Anabaptist faith perspective. Perhaps the institutional church we are all familiar with might be dying in Europe, but we believe the church as a body of believers will continue and maybe even become stronger...it just might evolve to look different than what we’re used to.

Our work right now is supporting a local Mennonite community in hopes of learning what it means to continue the church’s mission in this new landscape. And what’s that mission:

“Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you. And remember, I am with you always, to the end of the age.”

This is the church’s responsibility. Not to conquest the world and make like-minded believers, but to make “disciples” — people who desire to learn the ways of Jesus.

Sometimes seeing is believing. A couple of summers ago when we were visiting churches in the U.S., we made a video of our first two years in Barcelona. The reality is COVID-19 has actually kept us too busy to update it, but it should give a picture of what postmodern, post-Christendom missions can look like:

Earlier, we focused on some of the struggles of the church in Europe but, if we’re being honest, the institutional church in the United States doesn’t seem to be doing so hot either. Just like in Europe, more and more people call themselves Christians without resembling Christ in the slightest — neither in actions nor in words. For many, calling yourself a Christian has become more a declaration of social identity than a commitment to rejecting the values of empire and walking in Jesus’ footsteps.

I have enough friends who’ve walked away from the church to know that the word “Christian” doesn’t universally inspire hope anymore.

Even though we’re still early in what we hope to be a lifetime serving Spain, perhaps we’ve learned a few things that might be helpful stateside. For one, we’ve actually taken a rather non-Evangelical approach to the relationships we’ve been forming with folks outside our church community. By that, I mean we don’t think in terms of “making opportunities to convert folks” — that’s another way of describing conquest. Instead, we try to live transparently and speak with conviction when the appropriate times arise, while also listening a lot and simply investing time into building honest relationships.

In our last newsletter, Jon Chubb, a good friend and leader of our support team, put this approach into other words: “Rather than be content with, ‘Well, this is what has always been done,’ the approach has been more-so, ‘Well, how do we think Jesus would respond in this situation.’”

Reflecting Christ naturally through our actions (and words when necessary) has resulted in some intense relational developments after we had been here a while:

Alisha celebrates with her Spanish teacher after getting a hard-fought good test result.

When I was taking language courses, my Spanish teacher would often mention in class that she’s not religious. However, after about a year, she started to comment more and more that Alisha and I have confounded her stereotypes about what being a Christian can look like. She made me the authority of all things Christian in our classes, giving me a natural platform to share from a Christian faith perspective few other students had heard before.

One of the people we lived with in our church’s community house said knowing us proves to her that God is real. While living with her, we saw her slowly reconnect with her Orthodox Christian faith, but with a new Anabaptist flavor that compels her to “live it out” in her day-to-day life.

Another acquaintance has invited herself to our church. Twice. She told us she’s never met Christians that believe in science before and that she never would have considered going to a church until she met us. Interestingly, the impact we had wasn’t just on her, but also our local church community as they weren’t used to having anyone from their personal lives come to church.

These are just a few of many examples, but hopefully they paint a picture. God is moving. Us living our lives openly and with conviction in the places and circumstances we naturally find ourselves has been the conduit God uses to transform those around us.

Those that society calls privileged are those Jesus would call poor. Jesus teaches us to serve the poor. But God also needs us to save the “rich.” The world desperately needs communities and individuals that boldly proclaim Jesus’ countercultural, Empire-antagonizing message of reckless love and hope.

And so to those claiming the title of Christian, I say, “Church, that’s your job.”

Let me be very clear that what I’m not saying is that missional service to those suffering physical poverty is somehow less important than what we do, or that missions in economically poorer parts of the world are not needed. However, it’s important to acknowledge that society is changing and, in addition to the church, there are a lot of secular organizations that are doing amazing things to improve the quality of life for folks all around the globe.

I mean, do you need to know Jesus to be a good person and care about others?

But addressing spiritual poverty, which is spreading, is the church’s responsibility — nobody else is going to do that — and our understanding of missions must grow to encapsulate that need as well.

Attacking all forms of poverty

“What does spiritual poverty look like in my context?”

That’s the question I hope you’re asking yourself right now. Earlier, I used the word “church” in a non-corporate sense, addressing Jesus followers rather than the institution. That was very intentional. We must never forget “church” is something that we are together and not something we go to. Doing that allows us to tap into something vital in this postmodern world: the church as a body can go to the people. Buildings cannot.

And when we go carrying the light of Christ in our own lives, unexpected things tend to happen. Isn’t it interesting how COVID-19 has proved that we don’t necessarily even need buildings at all to be the body of Christ?

Over the last decade, we’ve had the privilege of visiting quite a few church communities to share about how we see God moving. And, while those visits are intended to be us encouraging them, it’s always amazing to see and hear how they’re engaging the community around them. Things like Mennonite thrift stores, meals for low-income families, after-school programs and tutoring for local youth, restorative justice training, language classes for immigrants — these types of programs can allow small churches to do a profound amount of good.

Growing up as an ethnic Mennonite, my experience has often been that we find it much easier to engage in service projects than share the more spiritual aspects of our faith. It’s left us as the harbingers of a different type of message for these churches: as you continue to think boldly and creatively about meeting the physical needs of those you encounter, we encourage you to think with the same boldness about the spiritual needs.

This is not a plea for capital-E-Evangelism. People can witness and experience your faith without feeling coerced into adopting it. But Spiritual Poverty is spreading and wreaking havoc. As we’ve watched from afar, it seems like the United States is increasingly becoming a place where fear and anger are causing good people to seek isolation and look to politicians for salvation. Embarrassingly, this seems to affect Christians and non-Christians almost equally. But we know the only real salvation comes from the deep spirituality that develops when you walk in the footsteps of Jesus.

And I think we can all agree that the world could do with more people trying to be like Jesus.

For all the folks you’re caring for and encountering in your daily life, you are the image of Christ. Lean into that. Be the Christ that not just heals physical ailments, but also tends to the spiritual wounds that keep folks from experiencing profound peace and liberation.

Our family and our community, we are the incarnation —the resistance — in Barcelona. Church, you are the incarnation in your community.

Note: This message is available as a virtual sermon. E-mail Gloria, Mennonite Mission Network’s church relations coordinator, at GloriaG@mmnworld.net if you’re interested in sharing it with your community.

When we arrived in the Czech Republic 10 years ago, we encountered young people who were feeling a deep spiritual longing but lacked the vocabulary or the guidance of healthy faith communities to find spiritual nourishment. And isn’t the definition of poverty not being able to get something you need to live fully?

Ergo, Spiritual Poverty.